Operation Husky The invasion of Sicily

In May 1943, the Ailed Army finally got the first taste of victory they was wanting for. In North Africa the Axis forces composed of more than 250,000 German and Italian troops that gave up at Tunisia. Through intense debates in the previous months, it had become apparent to the Allied leadership that the next step taken by the Allies would not be a cross-channel attack into northern France, as preparations for such an expedition would be inadequate and premature. Instead, the next major initiative against the enemy would come in a Mediterranean crossing that would seek the first defeat of one of the three Axis powers—fascist Italy.

Sicily was a natural route to mainland Italy and the European continent going back in history to the Punic Wars between Carthage and Rome. The Allies could count on air cover from Malta for a Sicilian invasion. In an elaborate espionage operation know as Mincemeat, designed to divert German defenses, British intelligence dressed a suicide victim as a Royal Marine, planted false papers on the corpse, and deposited the package off the coast of Spain for the Germans to find and interpret. The ruse proved successful, and German resources were shifted to the islands of Sardinia and Corsica.

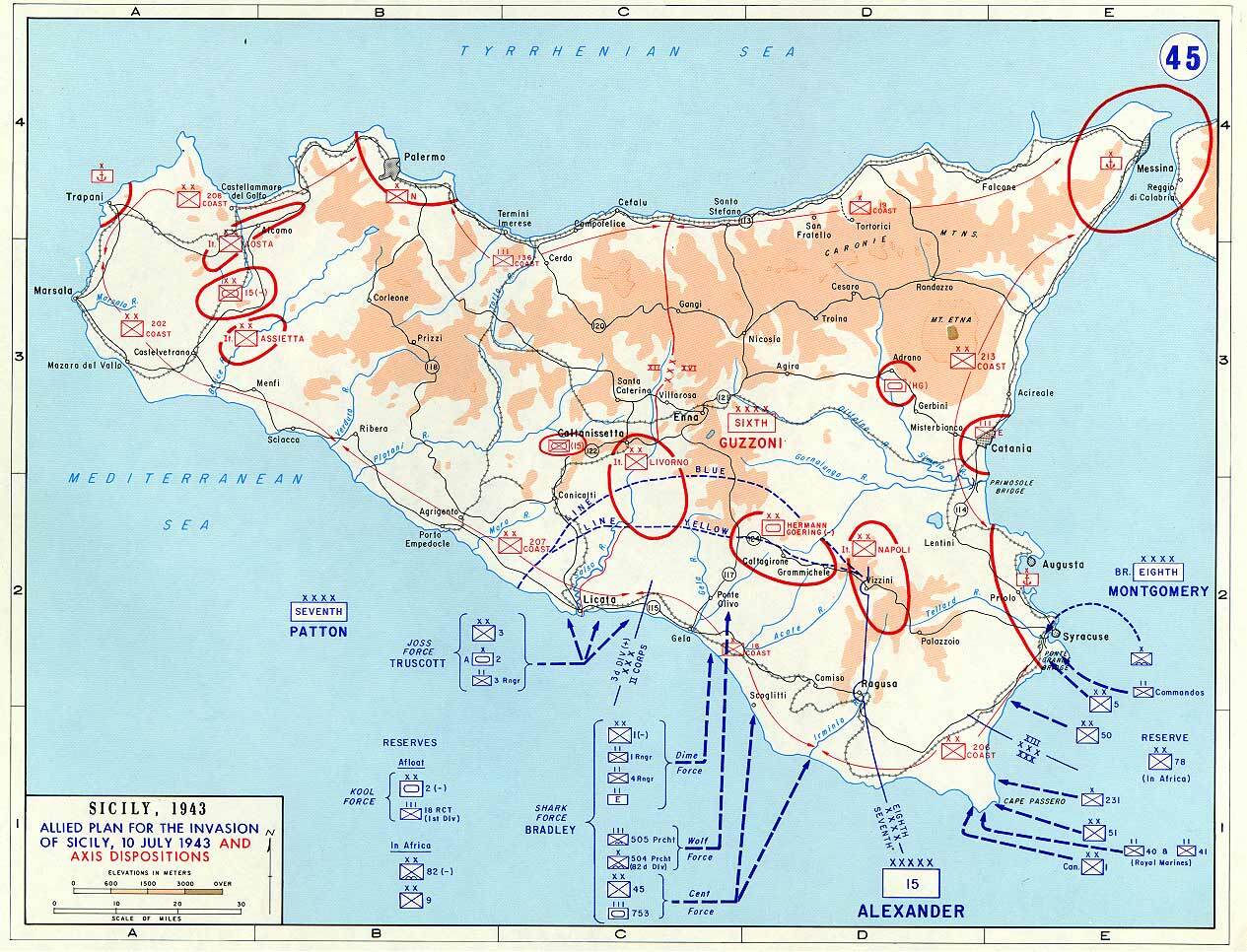

Problems of military coordination and logistics, although diminishing, continued to plague the Allied forces. Competitive egos also emerged in the Allied leadership. Lieutenant General George S. Patton landed with the US Seventh Army at Gela, while the British, under General Bernard Montgomery, led the Eighth Army to the east. Montgomery’s forces were charged with advancing up the eastern shore directly toward Messina. Meanwhile, Patton’s forces were charged with protecting Montgomery’s flank and moving to the northwest toward Palermo. They would then be positioned to advance east across Sicily’s northern shore to Messina.

In the immediate aftermath of the Allied landings, German General Albert Kesselring judged that the Italian fighting forces were so weak that the Germans were virtually on their own in the fight. Indeed, the Allies had believed that the Italian government was politically unstable, and they were not disappointed in that assessment. On July 24, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini was deposed and arrested under a new Italian government headed by Pietro Badoglio, who immediately began to seek peace terms with the Allied governments and withdrew Italian troops the next day.

Adolf Hitler was not as easily swayed, and ordered the German troops to continue strong resistance. Nonetheless, the die was cast for a German withdrawal from Sicily. When the Allies closed in on the port of Messina on August 17, 1943, they discovered the Germans had withdrawn more than 100,000 troops across the straights, reinforcing the Wehrmacht to continue the fight in mainland Italy. The northern campaign up the peninsula to free Italy and ultimately western Europe would prove an arduous task.

In 38 days, the Allies had taken the first major step along that continental road with the liberation of Sicily. The effort cost approximately 24,850 American, British, and Canadian casualties. Although there would be further twists and turns in the liberation of the Italian nation, through Sicily the Allies had successfully delivered a devastating blow against the first fascist government in world history when they toppled Mussolini’s regime.